The evolution of scientific impact

August 6, 2009 18 Comments

In science, much significance is placed on peer-reviewed publication, and for good reason. Peer review, in principle, guarantees a minimum level of confidence in the validity of the research, allowing future work to build upon it. Typically, a paper (the current accepted unit of scientific knowledge) is vetted by independent colleagues who have the expertise to evaluate both the correctness of the methods and perhaps the importance of the work. If the paper passes the peer-review bar of a journal, it is published.

Measuring impact

For many years, publications in peer-reviewed journals have been the most important measurement of someone’s scientific worth. The more publications, the better. As journals proliferated, however, it became clear that not all journals were created equal. Some had higher standards of peer-review, some placed greater importance on perceived significance of the work. The “impact factor” was thus born out of a need to evaluate the quality of the journals themselves. Now it didn’t just matter how many publications you had, it also mattered where.

But, as many argue, the impact factor is flawed. Calculated as the average number of citations per “eligible” article over a specific time period, it is highly inaccurate given that the actual distribution of citations is heavily skewed (an editorial in Nature by Philip Campbell stated that only 25% of articles account for 89% of the citations). Journals can also game the system by adopting selective editorial policies to publish articles that are more likely to be cited, such as review articles. At the end of the day, the impact factor is not a very good proxy for the impact of an individual article, and to focus on it may be doing science – and scientists – a disservice.

In fact, any journal-level metric will be inadequate at capturing the significance of individual papers. While few dispute the possibility that high journal impact factors may elevate some undeserving papers while low impact factors may unfairly punish perfectly valuable ones, many still feel that the impact factor – or more generally, the journal name itself – serves as a useful, general quality-control filter. Arguments for this view typically stem from two things: fear of “information overload”, and fear of risk. With so much literature out there, how will I know what is good to read? If this is how it’s been done, why should I risk my career or invest time in trying something new?

What is clear to me is this – science and society are much richer and more interconnected now than at any time in history. There are many more people contributing to science in many more ways now than ever before. Science is becoming more broad (we know about more things) and more deep (we know more about these things). At the same time, print publishing is fading, content is exploding, and technology makes it possible to present, share, and analyze information faster and more powerfully.

For these reasons, I believe (as many others do) that the traditional model of peer-reviewed journals should and will necessarily change significantly over the next decade or so.

Article-level metrics at PLoS

The Public Library of Science, or PLoS, is leading the charge on new models for scientific publishing. Now a leading Open Access publisher, PLoS oversees about 7 journals covering biology and medicine as well as PLoS ONE, on track to become the biggest single journal ever. Papers submitted to PLoS ONE cover all areas of science and medicine and are peer-reviewed only to ensure soundness of methodology and science, no matter how incremental. So while almost every other journal makes some editorial judgment on the perceived significance of papers submitted, PLoS ONE does not. Instead, PLoS ONE leaves it to the readership to determine which papers are significant through comments, downloads, and trackbacks from online discussions.

Now 2 1/2 years old, PLoS ONE boasts thousands of articles and a lot of press. But what do scientists think of it? Clearly, enough think highly of it to serve on its editorial board or as reviewers, and to publish in it. Concerns that PLoS ONE constituted “lite” peer review seem largely unfounded, or at least outdated. Indeed, there are even tales of papers getting rejected from Science or Nature because of perceived scientific merit, getting published in PLoS ONE, and then getting picked up by Science and Nature’s news sections.

Yet there is still feeling among some that publishing in PLoS ONE carries little or no respectability. This is due in part to a misconception of how the peer review process at PLoS ONE actually works, but also in part because many people prefer an easy label for a paper’s significance. Cell, Nature, Science, PLoS Computational Biology – to most people, these journals represent sound science and important advances. PLoS ONE? It may represent sound science but it’s up to the reader to decide whether any individual paper is important.

Why is there such resistance to this idea? One reason may be tied to time and effort to impact: while citations always have taken some time to build up, a journal often provides a baseline proxy for the significance of a paper. A publication in Nature on your CV is an automatic feather in your cap, and easy for you and for your potential evaluators to judge. Take away the journal, and there is no baseline. For some, this is viewed as a bad thing; for others, however, it’s an opportunity to change how publications – and people – are evaluated.

Whatever the zeitgeist in particular circles, PLoS is clearly forging ahead. PLoS ONE’s publication rates continue to grow, such that people will eventually have to pay attention to papers published there even if they pooh-pooh the inclusive – but still rigorous – peer review policy. Recently, PLoS announced article-level metrics, a program to “provide a growing set of measures and indicators of impact at the article level that will include citation metrics, usage statistics, blogosphere coverage, social bookmarks, community rating and expert assessment.” (This falls under the broader umbrella of ‘post-publication peer review’.) Just how this program will work is a subject of much discussion, and certain metrics may need a lot of fine-tuning to prevent gaming of the system, but the growing consensus, at least among those discussing it online, is that it’s a step in the right direction.

Essentially, PLoS believes that the paper itself should be the driving force for significance, not the vehicle it’s in.

The trouble with comments

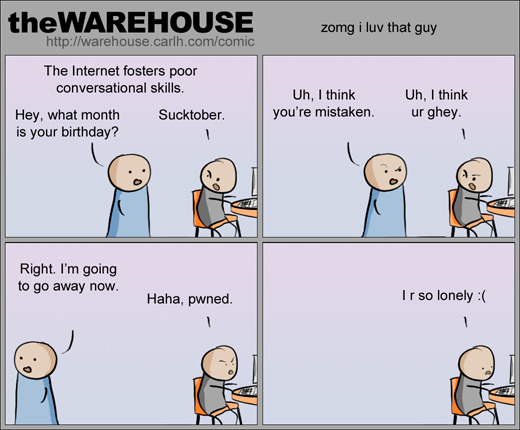

A major part of post-publication peer review such as PLoS’s article-level metrics is user comments. In principle, a lively and intelligent comment thread can help raise the profile of the article and engage people – whether it be other scientists or not – in a conversation about the science. This would be wonderful, but it’s also wishful thinking; as anyone who’s read blogs or visited YouTube knows, comment threads devolve quickly unless there is moderation.

For community-based knowledge curation efforts (think Wikipedia), there is also a well-known 90-9-1 rule: 90% of people merely observe, 9% make minor or only editorial contributions, and 1% are responsible for the vast majority of original content. So if your audience is only 100 people, you’ll be lucky if even one of them contributes. Indeed, experiments with wiki-based knowledge efforts in science have been rocky at best, though things seem to getting better. The big question remains:

But will the bench scientists participate? “This business of trying to capture data from the community has been around ever since there have been biological databases,” says Ewan Birney of the European Bioinformatics Institute in Hinxton, UK. And the efforts always seem to fizzle out. Founders enthusiastically put up a lot of information on the site, but the ‘community’ — either too busy or too secretive to cooperate — never materializes. (From a news feature in Nature last September on “wikiomics”.)

Thus, for commenting on scientific articles, we have essentially two problems: encouraging scientists to comment, and ensuring that the comments have some value. An experiment on article commenting on Nature several years ago was deemed a failure due to lack of both participation and comment quality. Even now, while many see the fact that ~20% of PLoS articles have comments as a success, others see it as a inadequate. Those I’ve talked to who are skeptical of the high volume nature of PLoS ONE tend also to view their comments on papers to be a highly valuable resource, one not to be given away for free in public but disclosed in private to close colleagues or leveraged for professional advancement through being a reviewer.

Perhaps the debate simply reflects different generational mindsets. After all, people are now growing up in a world where the internet is ubiquitous, sharing is second-nature, and almost all information is free. Scientific publishing is starting to change, and so it is likely that current incentive systems will change, too. Yet while the gulf will eventually disappear, it is perhaps at its widest point now, with vast differences in social norms, making any online discourse potentially fraught with unnecessary drama. As Bora Zivkovic mentions in a recent interview,

It is not easy, for a cultural reason, because a lot of scientist are not very active online and also use the very formalised language they are using in their papers. People who have been much more active online, often scientists themselves, they are more chatting, more informal. If they don’t like something they are going to say it in one sentence, not with seventeen paragraphs and eight references. So those two kinds of people, those two communities are eyeing each other with suspicion, there’s a clash of cultures. The first group sees the second group as rude. The second group views the first group as dishonest. I think it will evolve into something in the middle, but it will take years to get there.

When people point to the relative lack of comments on scientific papers, it’s important to point out the fact that online commenting has not been around in science for very long. And just as it takes time for citations to start trickling in for papers, it takes time to evaluate a paper in the context of its field. PLoS ONE is less than three years old. Bora notes, “It will take a couple of years, depends on the area of science until you can see where the paper fits in. And only then people will be commenting, because they have something to say.”

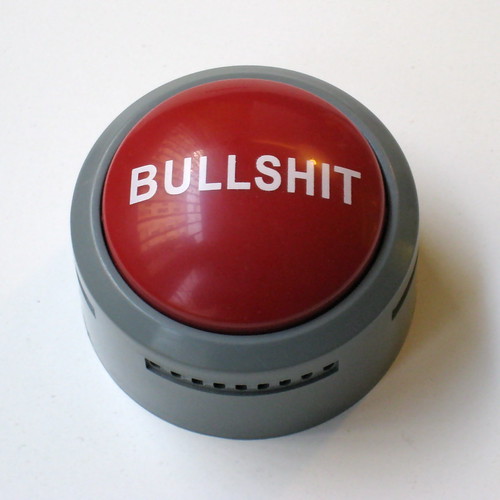

Brush off your bullshit detector

The last argument I want to touch on is that of journals serving as filter for information. With millions of articles published every year, it can seem a daunting task keeping up with the literature in your field. What should you read? In a sense, a journal is a classifier, taking in article submissions and publishing what it thinks are good and important papers. As with any classifier, however, performance varies, and is highly dependent on the input. Still, people have come to depend on journals, especially ones with established reputations, to provide this service.

Now even journals have become too numerous for the average researcher to track (hence crude measures like the impact factor). So when PLoS ONE launched, some assumed that it would consist almost entirely of noise and useless science, if it could be considered science at all. I think it’s clear that that’s not the case; PLoS ONE papers are indeed rigorously peer-reviewed, many PLoS ONE papers have already had great impact, and people are publishing important science there. Well, they insist, even if there’s good stuff in there, how am I supposed to find what’s relevant to me out of the thousands of articles they publish every year? And how am I supposed to know whether the paper is important or not if the editors make no such judgment?

Here, I would like to point out the many tools available for filtering and ranking information on the web. At the most basic level, Google PageRank might be considered a way to predict what is significant and relevant to your search terms. But there are better ways. Subscribing to RSS feeds (e.g. through GoogleReader) makes scanning lots of article titles quick and easy. Social bookmarking and collaborative filtering can suggest articles of interest based on what people like you have read. And you can directly tap into the reading lists of colleagues by following them on various social sharing services like Facebook, FriendFeed, Twitter, and paper management software like Mendeley. I myself use a loose network of friends and scientific colleagues on FriendFeed and Twitter to find interesting content from journals, news sites, and blog posts. The bonus is that you also interact with these people, networking at its most convenient.

The point is that there is a lot of information out there, you have to deal with it, and there are more and more tools to help you deal with it. It’s no longer sufficient to depend on only one filter, and an antiquated one at that. It may also be time to take PLoS’s lead and start evaluating papers on their own. Yes, it takes a little more work, but I think learning how to evaluate papers critically is a valuable skill that isn’t being taught enough. In a post about the Wyeth ghost-writing scandal, Thomas Levenson writes:

… the way human beings tell each other important things contains within it real vulnerabilities. But any response that says don’t communicate in that way doesn’t make sense; the issue is not how to stop humans from organizing their knowledge into stories; it is how to build institutional and personal bullshit detectors that sniff out the crap amongst the good stuff.

Although Levenson was writing about the debate surrounding science communication and the media, I think there’s a perfect analogy to new ways of publishing. Any response that says don’t publish in that way doesn’t make sense; the issue is not how to stop people from publishing, it is how to build personal bullshit detectors – i.e. filters. People should always view what they read with a healthy dose of skepticism, and if we stop relying on journals, or impact factors, or worse to do all of our vetting for us, we’ll keep that skill nicely honed. At the same time, we are not in this alone; leveraging a network of intelligent agents – your peers – will go a long way.

So continue leading the way, PLoS. Even if not all of the experiments work, we will certainly learn from them, and keep the practice and dissemination of science evolving for the times.

Thank you for providing such an elegant and detailed overview of the issues swirling around resistance to new forms of scientific publishing, problems with the impact factor, and arguments for and against online readership determining an article’s value — a very, very nice post.

I worry that the trend away from publicly commenting has nothing to do with the online nature of the comments you’re discussing here, and are instead more indicative of a larger trend in science. I regularly attend many biology meetings every year, and I can’t remember the last time someone in the audience asked a question challenging the results of a speaker. I’m a semi-old fogey, but years ago I remember the questions portion of talks at meetings serving as rousing debate sessions. Now it seems like there’s a general resistance to publicly call out a colleague or question their work in any way, even to offer constructive criticism. These sorts of discussions do still take place at meetings, but you instead see them at poster sessions, where there’s much more of an opportunity for one-to-one communication without either party exposing themselves to a large crowd.

It’s odd that in an age where we’re seeing more social networking, more openness, and more public communication, we’re seeing science trending in the opposite direction, towards more direct and private communication between individuals. I wonder if this cautiousness is a result of economic hard times, a limited number of jobs and a limited amount of funding making people afraid of controversy and the creation of enemies. Which makes me dubious that we’ll see strong uptake of public commenting features any time in the near future.

Good thoughtful article, I enjoyed reading it. I’d argue that although flawed, journals can serve as a valuable filtering method. Since every other method you mention has its own flaws as well, we’re better served with a variety of filters that can balance one another, and tossing out a proven method that has shown value over time in favor of unproven methods may not be the best way to go. The more tools and filters we have, the better.

Pingback: William L. Anderson (band) 's status on Thursday, 06-Aug-09 14:33:50 UTC - Identi.ca

@David, that’s a good observation. I wonder if the reluctance to speak out has anything to do with conferences getting bigger? Are smaller conferences like CSH and Gordon-types more conducive to actual discussion? Or perhaps science has become more competitive without retaining a common spirit of curiosity and inquiry?

You’re certainly right about filtering methods – there’s no one size fits all. I agree that many journals can be useful; for example, ones that you know are very in line with your interests. For more exploratory purposes, though, I would argue that Nature and Science’s low-throughput, high-breadth model may not be as useful as PLoS ONE’s high-throughput, high-breadth. And I certainly don’t see journals going away any time soon – rather, I hope that as gatekeepers of information they can adapt to help us find valuable information more quickly.

There’s a good post over at tomroud.com which talks about some of the dangers of “crowd-sourcing” impact and focusing on the paper. Mainly that exaggerated media/blog buzz can distort and distract subsequent evaluation of the paper (e.g. the “missing link” fiasco) and that a system that relies on comments and trackbacks is subject to popularity contests and public understanding of the subject matter. A paper about a more mainstream concept will necessarily receive more attention than an insightful paper about a very esoteric topic; is it fair to judge these two papers by the same metric? etc. I don’t think journals solve this problem better (impact factor will penalize journals with a more limited audience), but good points to keep in mind. (The blog is in French, but I used Google Translate.)

Many people worry about the popularity contest thing, and the answer is collaborative filtering (like you mentioned). Early internet-based metrics have indeed been crude popularity-based measures, but that’s just the beginning. The next step is to go beyond general popularity and instead specifically measure popularity among people who share your interests and values, as revealed by your and their ratings. Then you don’t have to worry as much about the rabble injecting noise into your info stream.

So I’d argue that we need to move beyond using just link structure (and tracebacks, etc.) that are just one bit of information, and go to netflix-style (or reddit/digg-style) ordinal ratings.

@David, I wonder if some of the resistance to “calling people out” is due to the fact that so many papers are produced by interdisciplinary teams of researchers, and individual researchers feel less inclined to tackle issues that bleed into areas outside of their own field of expertise.

@DeLene–I’m not sure that explains it. That would cover a certain segment of what’s published and presented, but there are still plenty of specialist meetings and papers out there and I don’t see anything different happening with them.

@Mitch–I worry that any ratings system would be very easily gamed. If Amazon’s ratings are any example, then it’s not the way to go.

Pingback: An alternate view of Peer Review? « A Current Opinion

Pingback: Mailund on the Internet » Blog Archive » Last week in the blogs

Pingback: Impact Factor Boxing 2009 « O’Really?

Pingback: ScienceBlogs Channel : Technology | blogcable

Pingback: The evolution of scientific impact | BenchFly Blog

Pingback: Recent links on Open Access « Free Our Books

I agree the answer to solving the problems raised by less filtered publishing is by collaborative filtering. One tool that does this successfully is Faculty of 1000 which uses pre-selected experts across Biology and Medicine (almost 5000 of them) who are thought-leaders in their area to keep an eye on all the literature and highlight to readers which papers are worth reading and why. This therefore essentially provides user comments, but moderated. Readers can then also post their comments as well if they want to add something. This is therefore a post-publication ranking system but that does not require the long wait for citation figures but merely for a Faculty Member to see the article and write their evaluation – a matter of a couple of months.

In fact, F1000 have found that about three-quarters of the papers that are selected by these experts are not in the generally recognised top 5 or so journals, proving that there is a lot of really top science published in much lesser journals and that it is all about the quality of the article itself and not about the journal it is published in that matters.

A nice article on F1000 Biology can be found at http://hypothesisjournal.com/index.php/main/article/view/36/36

Pingback: Science Spotlight – September 1st, 2009 | Next Generation Science

Pingback: A brief analysis of commenting at BMC, PLoS, and BMJ « I was lost but now I live here

Pingback: No comment « I was lost but now I live here